Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles, a life as patrons (permanent exhibition)

from 12 July to 20 September 2020

Exhibition not visible at the moment

With the support of CHANEL, main patron of the exhibition.

Despite a reputation whose importance never ceases to increase, nobody had ever devoted an exhibition to Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles, the renowned benefactors. Their name – which was associated with an impressive list of artists and intellectuals – is present in all of the works which discuss the period. Despite this, no attempt had been made to re-assemble and inventory the countless details and documents which relate to their involvement. Ever since the inauguration of the villa Noailles arts centre, the organisation in charge of its exhibitions had always intended to present this legacy in full view of the contemporary exhibitions. At the same time, there was an obligation to introduce people to the history, the architecture, and the furnishings of the villa Noailles. However, it was never simply a matter of handing over the the keys to understanding this “small, interesting home to live in”, in Hyères. Instead, the key issue was to also show how this building and its contents fit within a much greater ensemble: the extraordinary patronage that Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles undertook from 1923 to 1970. To unveil how the villa Noailles was the stage for artistic encounters, exchanges, and montages. A montage of images, ideas, periods, and legacies. Therefore, exhibiting how Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles expanded the definition of patronage in exploring all of its myriad forms. If this exhibition serves to place a spotlight upon that which they celebrated publicly, it also exposes all that they accomplished with the utmost discretion. Its aim is to expose the quality of this patronage and to make its magnitude felt, to put across the importance of the roles they played, in order to at last return them to their rightful position. A position that was central, at the heart of modernity, and that was the work of a lifetime.

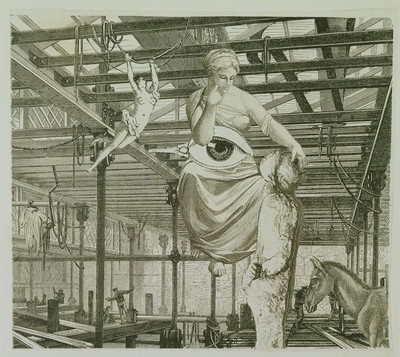

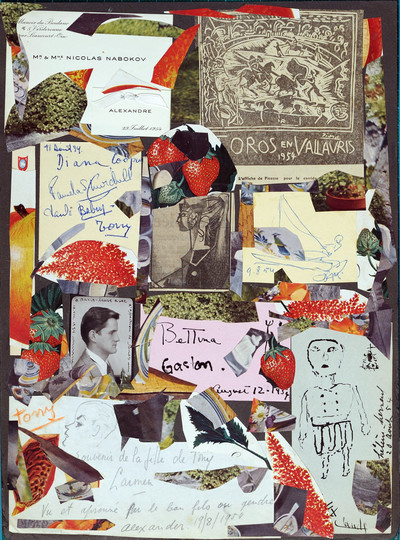

One might suggest that the distinguishing feature of their patronage, was its capacity to be in keeping with the tenets of their period, their era, or to quote Walter Benjamin, of the mechanical reproduction of the art work. Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles took an interest in ethnography, music, dance, cinema, photography, and literature, clearly understanding that collage and montage represented modernity itself; that synthesis creates meaning. Brecht, Vertov, Picasso, Eisenstein, Ernst, Bataille, Leiris, and Rivière were – as part of their many friends and acquaintances – the artists responsible for granting meaning to the legacies of Baudelaire, Manet, Proust, and Mallarmé – the pioneers who had paved the way for montage on the eve of the 20th Century. Marie-Laure de Noailles combined images and texts in her scrapbooks, accumulated antique sculptures, works by Goya, Dali, and Rubens, snow globes, Spanish dolls, and fifty or so postcards, all on the same wall, like a Wunderkammer. A cabinet of curiosities, an experimental space, where subjects and objects are combined with one another, operating an incessant interlacing of significations. In fact, Marie-Laure de Noailles experimented for herself with this free association – as favoured by the Surrealists – whilst developing her own path too. She more or less consciously produced a quasi-systematic confrontation between high and low culture, thus granting her installations a dimension that was unique in the patronal milieu of the 20th Century; or as Benjamin wrote: freeing the artistic work from its parasitic existence in a ritual.

Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles grasped that modernity was a combination of numerous influences, a montage of forms, seemingly unsuited towards coexisting in the same space; as expressed in both the construction of the villa, or its interior design, which in itself arose out of a montage of furnishings that were the product of the most diverse trends. Consequently, they freely combined furniture by Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann, Jean-Michel Frank, Charlotte Perriand, and Francis Jourdain, with industrial fittings, created by Smith & Co and Ronéo, alongside period pieces.

When Charles de Noailles offered his support to the key artists behind the periodical Documents (Bataille, Leiris, Desnos, Limbour, and the photographer Boiffard), he intuitively grasped that future intellectual and artistic revolutions would build not only upon the legacy of Surrealism, but even more so upon the founders of this periodical which incorporated: Documents, doctrines, archaeology, fine arts, ethnography, and entertainment. In short, that modernity was an encounter of influences which, through their intertwining, resulted in the emergence of a rhizomatic dialogue, no longer concerned with a segregation of disciplines.

A rootstock of which Charles and Marie-Laure were not just patron-spectators, but central actors instead. Thus, as already mentioned, they were in this respect at the very heart of modernity, or more precisely modernities, as their support did not stop – as has often been written – on the eve of the Second World War, but instead continued long after. These intellectual and artistic roots extended further still as, up until the 1970s, new generations of artists invited into their close network of friends, continued to explore the paths opened up by their precursors. Hence, Mandiargues, Clémenti, and César, illustrate between the three of them the artistic lineage between the artists of the 1920s, and those of the late 1960s, for whom Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles served as conveyors, always evolving and in pursuit of new trends. In fact, it is not unfitting to think that Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles chose to live not at the heart of the avant-garde, but within the Avant-gardes themselves.

Since 2010, the curatorial team composed of Stéphane Boudin-Lestienne and Alexandre Mare, under the direction of Jean-Pierre Blanc, has produced numerous thematic or monographic exhibitions related to the place and the patronage of Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles.

In 2018, the art centre will publish a beautiful book, the fruit of ten years of research it has funded, in co-edition with Bernard Chauveau.

2019

Elise Djo-Bourgeois

Jean Hugo magicien

2018

Picasso and the Noailles

2017

Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles, 20th century patrons in the collection of the National Museum of Modern Art

Jean Cocteau

2016

Robert Mallet-Stevens

Georges Hugnet

2015

The making of an image, Noailles and Fashion

Scrapbooks

2014

The ghosts of our past actions, Marie-Ange Guilleminot

Critical update

2013

Guy Bourdin

Marcel Breuer

2012

Mission Dakar-Djibouti

2011

Jacques Lipchitz

2010

inauguration

2009

prefiguration of the permanent exhibition

Djo-Bourgeois Architecte et décorateur

2008

Modern gardens

2006

The categorical admission of the material metal furniture 1925-39

2005

Colour in space, Dutch avant-garde in France

2004

The machine-light, modern luminaires of the years 1920-1930

2003

The villa Noailles

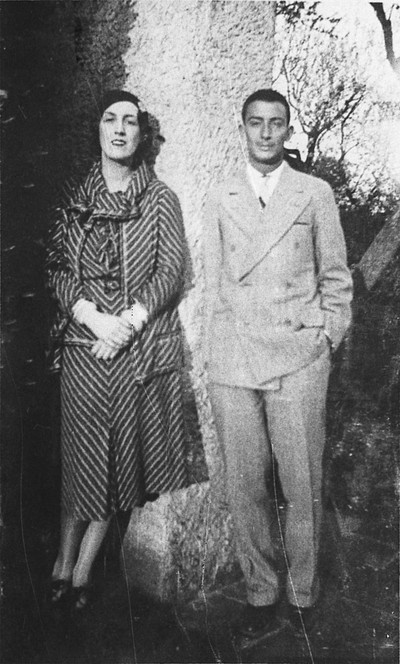

Marie-Laure Bischoffsheim (1902-1970) was only two years old when her father, Maurice, passed away, leaving her to inherit a considerable family wealth, along with an outstanding collection of paintings belonging to her grandparents. Two individuals in particular had a marked influence on her youth: her grandmother, Laure de Chevigné, whose modern attitude inspired Proust’s Duchess of Guermantes, and a young poet, called Jean Cocteau, who was to be instrumental in introducing her to the avant-garde of pictorial, musical, and literary arts.

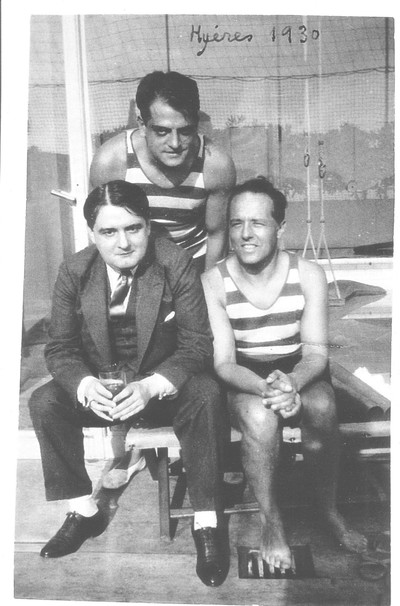

Following the Great War, Charles de Noailles (1892-1981) regularly attended the salons of the count de Beaumont, as did Marie-Laure. The de Noailles lineage, which may be traced back to the Crusades, is scattered with well-known figures, throughout the different periods. Charles de Noailles was to take particular interest in the contemporary decorative arts, architecture, and horticulture. It was upon these shared passions that their relationship was to form, and in February of 1923, they married in the Provençal town of Grasse.

They perused through the salons and exhibitions of 1925, acquiring furniture and paintings, meeting designers, and consequently, re-furnished their private residence on the place des États-Unis, Paris. Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles rapidly developed their own style and, after only a few years, had already made an impression in both the press and artistic circles as two of the most active and interesting benefactors of the second half of the 1920s. The start of the next decade was to see even more ambitious projects, but equally a slowing down of their support, following the scandal provoked by the film, L’Âge d’Or (Age of Gold). The viscount’s patronage continued, but was now more discrete in nature. Marie-Laure de Noailles, on the other hand, stepped out from her usual reserve and started to write, to paint, and received more artists and writers in her home than ever before.

If the Second World War was to mark the end of an era, then Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles emerged from it with their aura intact. The viscount now seemed more interested in his gardens and in his house in Grasse, but he continued to watch over those projects which were close to his heart. Marie-Laure, however, followed with a passion the artistic trends of her time and continued to receive her artist and literary friends, in both Paris and in Hyères. Marie-Laure de Noailles supported many young artists up until her death, in 1970.

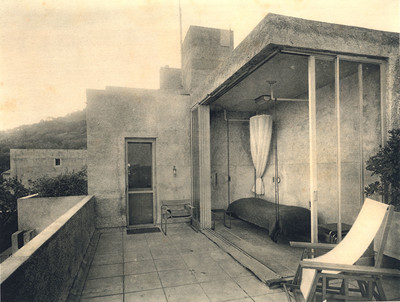

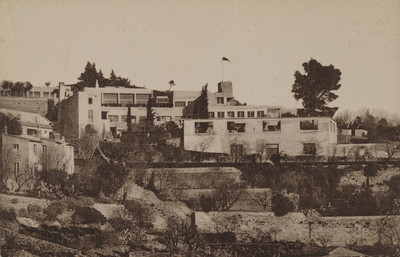

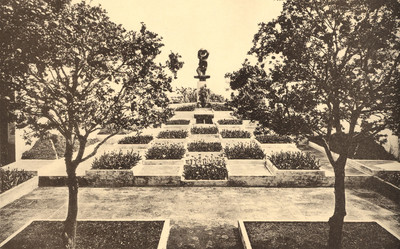

The villa Noailles, built between 1924 and 1932, is one of the most revealing examples of the new techniques developed by modern architects in the Interwar period, in France. The project was entrusted to the architect Robert Mallet-Stevens, for whom this was to be his first completed commission. He initially proposed a plan for a vast building on two floors, overlooked by a belvedere. A second plan, more compact, eventually satisfied the requirements of Charles de Noailles, who wished above all for a practical building: “a small, interesting home to live in”. Consisting of five bedrooms, a living room, and a dining room, the project seemed modest for clients such as the viscount and his wife. It fulfilled the period’s requirements for healthy living, as each room had its own terrace and bathroom. All of the living areas faced due South, whilst all of the corridors were pushed towards the North. If at first the cubic shapes were without a décor, the building was still subject to the relationship between its proportions and rhythms. The interaction between full and empty spaces, the repetitions of forms, and the cantilevered awnings, all evoked an affinity with the Neoplasticism of the Dutch De Stijl group.

Despite the architect’s wishes, when construction began in April of 1924, it was to exclude the reinforced concrete he had requested, as the local builders had not yet mastered its use. During construction work, the viscount decided to abandon the plan for a belvedere – much to the architect’s dismay – , and asked him to design a wall pierced with great picture windows, to enclose the courtyard facing the villa.

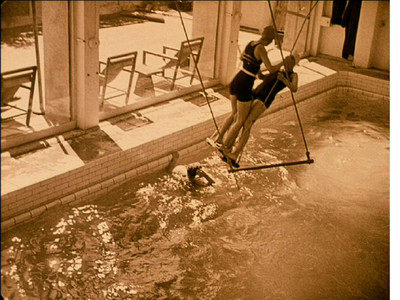

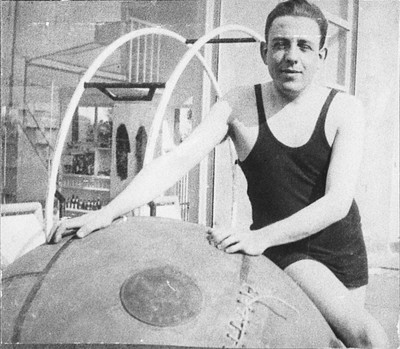

Pleased with the result, they ceaselessly extended and transformed the building, up until 1932, extensively modifying the initial plan. Thus, an annexe consisting of four bedrooms was added in 1925, followed by a second annexe in 1926, attached to the first by means of a covered staircase. The following year, Mallet-Stevens designed a surprising, three dimensional décor for the new Pink living room. During the same period, the construction of a sizeable pool room was undertaken, this time partially constructed out of reinforced concrete, comprising of a large pool and a ceiling made of glass bricks, forming a stunning geometrical composition. The south façade of the pool room, with its four, monumental, sliding picture windows, granted supremacy to all that was made of glass, over everything else. A gymnasium, followed by a squash court, completed the sports facilities. With fifteen master bedrooms and guest houses, the villa as a whole covers almost 1800m2 of living space.

The commissioning of a modern residence led Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles to design an interior in accordance with this new architecture. The majority of the chosen designers were recommended by the architect Robert Mallet-Stevens, who was also responsible for designing the pool room deckchairs. The interior décor consisted of both specific commissions for individual rooms – such as the dining room, which was entrusted to Djo-Bourgeois as early as 1924 –, as well as a concerted programme of acquisitions.

The furnishing of their villa occurred over a number of stages, as the couple were to accord themselves the time necessary for visiting the exhibitions, in order to find the designs they wished to incorporate. For example, a dial, designed by Francis Jourdain and discovered at the Autumn Exhibition of 1922, served as the inspiration for the villa’s clocks. The International Exhibition of Decorative, Industrial, and Modern Arts of 1925, was to reveal itself as a genuine source of inspiration, leading to the acquisition of a hanging bed by Pierre Chareau, stools by Mme Klotz, and “simultaneous” fabrics by Sonia Delaunay, which were literally transposed to their villa in Hyères.

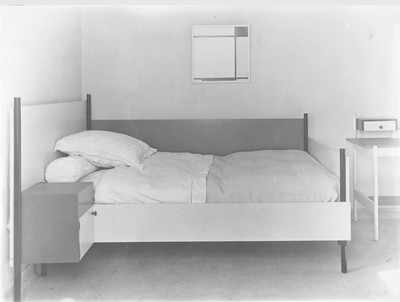

The villa was home to both extremely refined designs, such as a rug by Eileen Gray for Marie-Laure’s bedroom, or a folding games table by Charlotte Perriand, as well as more industrial furnishings, manufactured by firms such as Smith & Co (for the armchairs) and Ronéo (for the sheet metal tables and cabinets). Chareau’s inventiveness consorted with the elegance of Dominique. Louis Barillet was to create the stained glass ceiling and the Martel brothers designed a polyhedral mirror. The foldaway ironworks, designed by Jean Prouvé for the open-air bedroom, housed the furniture constructed of metallic tubes, designed by Marcel Breuer.

Two particular commissions, entrusted to Dutch artists, were notable for their radical nature. In 1925, the artist and theoretician, Théo van Doesburg, was assigned with the composition of a geometric mural for the flower room and the architect Sybold van Ravesteyn was to create the entire design for the guest bedroom on the second floor. The French designer, Djo-Bourgeois, was often sought, particularly in 1926, with the extension of the dining room and the creation of four further bedrooms with fitted furniture. He was also to design an ingenious and colourful bar for the vaulted rooms in the annexe.

Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles were patrons with a keen interest in artistic trends, thanks to the advice they received from Cocteau, Zervos, Rivière, and Leiris, as well as their attendance at some of the best galleries and publishers. As both collectors and commissioners, they offered their support to certain artists through the regular acquisition of works, or by offering them a monthly revenue along with other benefactors (such as the Zodiac Group), as was the case for Dali and Balthus. They frequently provided support that was not only remarkable, but also selfless: the viscount was to act as guarantor for the acquisition of Balthus’s home and Marie-Laure donated a Zil to César, allowing him to undertake his first ‘Compression’ of a motor car.

Whilst their taste, at least initially, encompassed established artists, Cubists, and members of the Paris school, such as Chagall, Braque, Lipchitz, Gris, Léger, Derain, de Chirico, and Picasso, the arrival of Surrealism in the 1930s offered a new direction for both their collection and their patronage. Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles acquired numerous works by Miro, Tanguy, Masson, Klee, Ernst, and Dali, as well as works by young emerging artists such as Nicholson, Toyen, and Styrsky. Their attendance at some of the key exhibitions of the period resulted in a number of major acquisitions. Hence, at the exhibition l’Art d’Aujourd’hui (Art Today) in December of 1925, they bought a work by Mondrian, making them one of the painter’s rare clients in France. Brancusi was exhibiting a Bird in Space at this exhibition and the couple asked him to examine creating a monumental example for their villa. Lipchitz received his first commission for a monumental cast bronze sculpture from the viscount and his wife, who also placed numerous commissions from Laurens. They discovered Alberto Giacometti early on in his career, in 1929, following one of his very first exhibitions.

A lengthy series of portraits of Marie-Laure de Noailles, initiated by a sketch by Picasso in 1921, illustrates her lifelong personal relationship with artists such as Dora Maar, Bérard, Balthus, Giacometti, Fenosa, and Valentine Hugo. She also posed in front of the lenses of some of the greatest photographers of the time: Horst, Hoyningen-Huene, Durst, Beaton, Doisneau, Brassaï, Rogi André, Chadourne, Maywald, and of course Man Ray, who created at least ten different series with her portrait as its subject.

Even though other patrons took an interest in avant-garde cinema, it would seem that Charles and Marie-Laure’s investment in this art form was beyond compare. At the beginning of 1928, they were to commission a film by Jacques Manuel called Biceps & Bijoux (Biceps & Jewellery) in which, surrounded by their friends on holiday, they amuse themselves by performing a more or less improvised scenario. Strictly intended for private viewing and despite its formal awkwardness, this film offers a unique account of their lives. In November of 1928, Man Ray was commissioned to direct an entirely more ambitious film. Les Mystères du Château de Dé (The Mysteries of the Château of Dice) staged a bold relationship between the architecture and a ceaselessly moving camera. The film was screened in June of 1929 at the Studio des Ursulines.

They met Jean Lods and Boris Kaufman as a result of their belonging to one of the first film clubs, Les Amis de Spartacus (The Friends of Spartacus). Consequently, the viscount was to join with Étienne de Beaumont in financing their first films, Vingt-quatre heures en trente minutes (Twenty-four hours in thirty minutes, 1928) and Champs-Élysées (1929). These films are now lost, but one may surmise that they were directed in a similar vein to the concepts of Cine Eye by Dziga Vertov, Kaufman’s brother. Despite not having commissioned Salvador Dali and Luis Buñuel’s film Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog), they were key to its success by screening it in their own private cinema (the first in France) which they had installed in their private residence. It was also screened at the Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier, alongside the other films which had benefited from the viscount’s influence.

Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles gave Buñuel carte blanche for his second film, L’Âge d’or (Age of Gold), whose screenplay was completed at the villa in Hyères during the winter of 1930. The shoot was to take place at the same time as that of Jean Cocteau’s début film, Le Sang d’un Poète (The Blood of a Poet), which was also financed by the couple and who had now become genuine “producers”. However, in 1931, following the public release of l’Âge d’Or, a shameful campaign resulted in the film being removed from distribution for half a century; this scandal resulted in a sudden end to their patronage of cinema. Cocteau’s film, on the other hand, was hailed for its visual and poetic inventiveness when it was screened in December of 1931.

At the end of the 1960s, Marie-Laure de Noailles encouraged the actor, Pierre Clémenti, to start directing his own films which, through their succession of images and through their montage, were not entirely without recalling the lost works of Lods and Kaufman, the Surrealist’s collages, or even the scrapbooks created by the viscountess herself.

Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles had numerous friendships in literary circles, amongst which one might mention writers such as Jean Cocteau – a childhood friend of Marie-Laure’s –, Marcel Jouhandeau, Aldous Huxley, François Mauriac, René Char – from whom they were to acquire the manuscript for Marteau sans maître (The hammer without a master) – Georges Hugnet, and André Pieyre de Mandiargues. Then there were editors, such as André Gide, Jean Schlumberger, and Jean Paulhan – with whom Charles de Noailles was to correspond for over thirty years –, who were key figures at the NRF (New French Review) periodical and the publishers Gallimard, as well as Marcel Raval, publisher and director of the periodical Les Feuilles libres. All of these friendships resulted in Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles making new acquaintances and frequenting new schools of thought and writing.

This support covered the full gamut of Surrealism: André Breton, Paul Eluard, or even René Crevel, who was also a close friend. However, it was their friendship with the museologist Georges-Henri Rivière which contributed most in surrounding the couple with other intellectuals and alternative philosophies of thought. Rivière was the kingpin behind the projects of the ethnographic Mission of Dakar-Djibouti, in 1931, as well as the creation, in 1937, of the Musée de l’Homme (Museum of Man), with which Charles de Noailles was actively involved. Without taking sides, the couple also supported the intellectual revival which emerged from the periodical, Documents, created in April of 1929, by acquiring manuscripts by writers such as Michel Leiris, Robert Desnos, Georges Limbour, and Georges Bataille (in particular that of Story of the Eye) for their collection. Embodying a form of resistance to Surrealism – as conceived of by Breton –, Documents was to play an important role in the evolution of contemporary thought, positing a protean and multi-cultural montage; an anthropological project the likes of which had not been seen before.

In a similar manner, at the end of the 1920s, Charles de Noailles mandated Maurice Heine to acquire the manuscript for 120 Days of Sodom, by the marquis de Sade, Marie-Laure’s ancestor. This key manuscript allowed for Heine to continue his work upon Sade, re-establishing him within the Age of Enlightenment and making new inroads in the history of 20th Century thought.

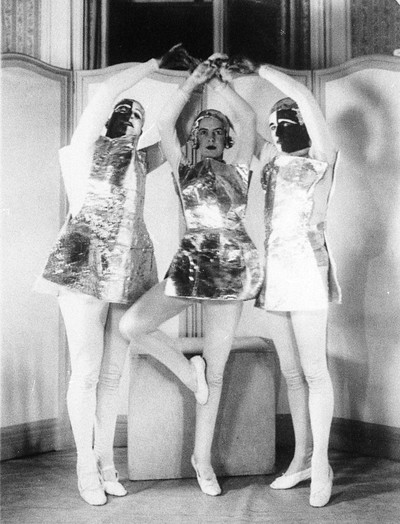

During the Interwar years, Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles organised themed balls. Many of these soirées offered an opportunity for the commissioning of new works from artists, as well as musicians and dancers, in order to promote their talents. One such example was the ballet, Aubade, commissioned from Francis Poulenc for the Bal des Matières (Materials Ball), and performed at their home on the place des Etats-Unis, in June of 1929, before being reprised at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées the following year. They also commissioned Georges Auric to compose his first cinematic soundtrack for Cocteau’s debut film; he was subsequently to write in excess of one hundred more.

In 1931, the viscount and his wife participated in the creation of the La Sérénade group and concert series, founded by Yvonne de Casa-Fuerte. Through this series – under the artistic direction of the conductor Roger Desormière – they contributed in both the production and distribution of works. Thus, the following year, a concert was given in April of 1932 at Hyères, for five works they had specially commissioned. In December of the same year, they financed the German composer Kurt Weill’s visit to Paris, along with his musicians for the Parisian premières of two works written with Brecht, Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny) and Der Jasager (The Affirmer), they also provided him with accommodation, during his exile, in 1933.

Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles, without asking for anything in return, were to provide Markevitch and Sauguet with the regular financial support they required for the completion of important works such as: the symphonic cantata Le Paradis Perdu (Paradise Lost) for the former, written in London, in 1935, and the opera la Chartreuse de Parme (The Charterhouse of Parma) for the latter, completed in 1936. Darius Milhaud was also to receive a commission for a cantata, for the opening of the Musée de l’Homme (Museum of Man), in 1937.

Though Marie-Laure de Noailles keenly followed the career of her friend ,the dancer Serge Lifar, it was after making the acquaintance of Boris Kochno that she was to offer her support to some of the great choreographic projects of that time: the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, under the leadership of Massine, Edward James’s Les Ballets 33, and Roland Petit’s Ballets des Champs-Élysées. Over the course of her life, Marie-Laure de Noailles also surrounded herself with the friendship of numerous, internationally renowned performers, such as: the pianists Jacques Février and Arthur Rubinstein, the cellist Maurice Gendron, the flautist Jean-Pierre Rampal, and the harpsichordist Robert Veyron-Lacroix.

1927: Paul Rivet is named as the director of the dusty Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro (Ethnographic Museum of the Trocadero) in Paris. At the same time Charles de Noailles assumed the leadership of the museum’s Society of Friends (SAMET) in order to further its development. The viscount presented to Rivet a young art critic – who was also a jazz pianist and an amateur songwriter for Joséphine Baker – his name was Georges Henri Rivière. He in turn called upon a new generation of scientists and intellectuals, thus turning the museum into a driving force for research and education. His objective was evident: to demon- strate how the world is full of different peoples with complex cultures, and that it was appropriate to study them on an equal human level; a position that was antithetical to both colonial politics and racial preju- dices. Influenced by Marcel Mauss – the theorist responsible for modern ethnography – they aimed to establish a form of ethnological investigation which focused on both the tangible and the intangible, rather than simply a “harvesting” of objects, which had previously been the typical approach. These avant-garde notions were supported in particular by contributors working for the review Documents, amongst whom, besides Rivière, were intellectuals such as Michel Leiris, Carl Einstein, and Georges Bataille.

In order to complete the museum’s collections the ethnologist Marcel Griaule offered to lead a mission between Dakar and Djibouti. The Noailles welcomed this adventure enthusiastically, as it represented a uniting of literary and artistic worlds with that of scientific research. Some of the participants were close friends, such as Leiris, the painter Gaston-Louis Roux, and the musicologist André Schaeffner. In 1931, in order to finance the mission, Rivière organised a boxing competition headlined by the world champion Panama Al Brown, and for which the Noailles bought a large number of the seats. After eighteen months, the mission’s outcome was a success: Three thousand five hundred objects, three hundred recordings, thou- sands of records, as well as manuscripts which allowed for a better understanding of this part of the African continent.

Charles de Noailles, through the SAMET, provided constant support for the museum’s development, offer- ing display cabinets, financing renovations, exhibitions, and acquisitions. In 1936, the former Palais du Trocadéro became the Palais de Chaillot. In 1937 the museum was rearranged and renamed as the Musée de l’Homme (Museum of Man). For its opening the viscount and Henri Monnet (chairman of the Symphonic orchestra of Paris) commissioned Robert Desnos (writer) and Darius Milhaud (composer) to compose the Cantate de l’Homme, thus inaugurating this new era. 1939: Charles de Noailles’ own mission seemed completed and he stepped down from his role having been a key figure alongside Rivet and Rivière in the establishment of modern ethnography.